KIVLAND, Sharon (2020). La Forme naturelle. [Show/Exhibition] [Show/Exhibition]

Documents

26541:550778

Image (JPEG)

Unknown-2.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Unknown-2.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (146kB) | Preview

26541:550779

Image (JPEG)

Unknown-8.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Unknown-8.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (172kB) | Preview

26541:550780

Image (JPEG)

Unknown-3.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Unknown-3.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (203kB) | Preview

26541:550781

Image (JPEG)

Unknown-4.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Unknown-4.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (238kB) | Preview

26541:550782

Image (JPEG)

Unknown.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Unknown.jpeg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (249kB) | Preview

26541:550793

Image (JPEG)

Readers.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Readers.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (662kB) | Preview

26541:550808

Image (JPEG)

Liquette Ninque VIEW.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Liquette Ninque VIEW.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (1MB) | Preview

26541:550809

Image (JPEG)

La Femme-Renarde (view).jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

La Femme-Renarde (view).jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (1MB) | Preview

26541:550818

Image (JPEG)

Corset & bird 01.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Corset & bird 01.jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (1MB) | Preview

26541:550823

Image (JPEG)

La Femme-Renarde (view 02).jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

La Femme-Renarde (view 02).jpg - Accepted Version

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (5MB) | Preview

Abstract

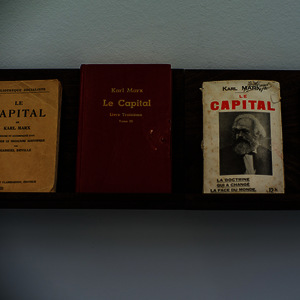

The works on display and their arrangement have been conceived for the space of Edizioe Periferia. They may be considered as a series of staging, concerning feminised reading, sexuality, and education. Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary and Karl Marx’s Capital are central texts, provide a logical pairing in the spectre of social boundaries failing to hold, when what is private and what is public are no longer separate spheres. The first takes up the staging of the affliction of the woman reader, for Emma Bovary reads too much and her reading is bound to lead to trouble (‘her over-exalted dreams, her too cramped house [les rêves trop hauts … la maison trop étroite’ ]. In reading Capital, women readers are equally dangerous. Reading women have subversive potential, and reading leads to errancy and transgression.

In the hall women’s knickers, antique, pink silk, embroidered in red soie de Paris in Ecolier script, with the phrase je suis une femme modern are suspended in beaks of birds (a buzzard, a jay, a thrush, a pair of doves…).

If the visitor continues through the silk and birds, s/he will arrive at something a little like a schoolroom. Eight wooden chairs are arranged on red glacé leather skins. From each chair hangs a blousons d’écolier, the smock or overall uniform that is no longer worn in schools. On each of eight chairs there is a squirrel holding in its dear little paws culottes in varying shades of pink, embroidered in red soie de Paris and Écolier script, with a phrase signifying the lovely object that is the commodity, showing the mutable forms taken by mademoiselle la marchandise. On each chair is a paperback copy of Madame Bovary, each cover giving a certain impression of ‘Emma’, according to the time it was published. On a school desk a less diligent squirrel has made a bed of Capital, and fallen asleep, her embroidery (a handkerchief: la forme naturelle) unfinished. On one wall, there is row of eight books on a lectern, paperback copies of Capital. Around the other walls runs a frieze of black and white posters depicting alternately the faces of young girls and the silk and lace-clad torsos of women, take from French fashion journals of the 1950s. It is as if the girls are looking for models in the corps morcélés.

If the visitor turns instead to the room on the right, there is a display of four series of drawings in ink and watercolour on pages torn from old school exercise books:

Liseuses de Capital depicts women with bobbed hair in négligés and bed-jackets, reading and dreaming, their cheeks a little flushed, reclining in bed. Their bed-jackets are liseuses in French. If their outfits, those light garments for women described in a masculine term, are feminised: négligées, they become those who demonstrate lack of care or do not take sufficient pains or wear a garment that barely covers them. Their books have red covers. Goodness, we certainly know what kind of books have red covers; they are not novels, pernicious enough, but equally dangerous. Is it a solitary pleasure? Are their hands lightly below the sheets? Are they educating themselves? Do they dream of political action, of new kinds of subjectivity?

Femmes-Renardes depicts women from behind, wearing pink slips that are cut to allow their bushy tails to emerge. Their hairstyles are rather foxy too, as is the hair under their arms. They may be a woman turning into a fox or a fox turning into a woman. They too are mutable.

Liquettes ninque depicts women with snakes. They are clearly taking great pleasure in each other’s company. The title is a hapax legomenon from Raymond Queneau’s novel Zazie dans le metro, a story about a young girl’s first visit to Paris. It occurs in a discussion about laundry, the recurrence of dirt, as a play on words. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan refers to it in relation to the phallus and the snake (he is discussing the hallucinated sakes of Anna O in Freud & Breuer). The snake, he says, is a symbol of the phallus and of nothing else. Like the devilish emptiness of dirt, the phallus never stops rewriting itself, here and now.

Les premier rouges depicts young girls wearing the New Look, Dior’s image of radical femininity, achieved by tight-fitting jackets with padded hips, petite waists, and A-line skirts. The clothes have been coloured in with red lipstick, the grease of which oozes through the paper.

On a long and exceptionally lovely wooden table in front of these drawings are four paired creatures, snake and mongoose. Two mongooses are fighting off reared cobras with a copy of Freud’s Trois essais sur la théorie sexuelle, while two others have failed in their struggle, their opened books cast aside as serpents entwine their bodies.

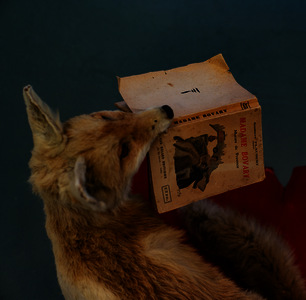

At the door, to one’s right, one is greeted by a fox head, holding an embroidered silk bedjacket, a liseuse, in his jaws. The text is taken from a strange tract written by Sylvain Maréchal in 1801, entitled Plan for a law forbidding a woman to learn to read (1801), which consists of eighty-two clauses, fortified by a hundred and thirteen reasons for the law, to prove that the woman who knows the alphabet has already lost a portion of her innocence (his friend and biographer Madame Gacon Dufour declared that he must be partially insane), in acquiring excessive education, linking innocence and ignorance, carnal knowledge and book knowledge. I am convinced the tract is a masterpiece of irony.

In the library to the left of the hall, five short films, entitled Coquetteries, play endlessly, for a single viewer seated in a beautiful armchair. In each, a single page in a French lingerie magazine is tracked from neck to knee or foot, slipping over and down the garment, a negligée, accompanied by a voiceover reading a description of the lingerie trends of the season. The sound seeps through the entire space of Periferia.

For the accompanying edition, ten booklets are boxed with an antique handkerchief embroidered by the artist in red soie de Paris and Didot script, each with a characteristic of the commodity ( « naturelle », « phénomenale », « sociale », etc.).

Some notes on embroidery:

Women once learnt to read through embroidering, as art or craft or labour, women’s work in any case, where the skill of the needlework was more important that the mastery of cursive script. There was a time that only the catechism and needlework were taught, but some demanded more, to be taught about everything. They read, and they learnt quickly. They understood forms. They assumed forms.

More Information

Statistics

Downloads

Downloads per month over past year

Share

Actions (login required)

|

View Item |

Tools

Tools Tools

Tools![[thumbnail of Unknown-2.jpeg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/1.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Unknown-2.jpeg)

![[thumbnail of Unknown-8.jpeg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/2.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Unknown-8.jpeg)

![[thumbnail of Unknown-3.jpeg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/3.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Unknown-3.jpeg)

![[thumbnail of Unknown-4.jpeg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/4.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Unknown-4.jpeg)

![[thumbnail of Unknown.jpeg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/5.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Unknown.jpeg)

![[thumbnail of Readers.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/16.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Readers.jpg)

![[thumbnail of Liquette Ninque VIEW.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/31.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Liquette%20Ninque%20VIEW.jpg)

![[thumbnail of La Femme-Renarde (view).jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/32.hassmallThumbnailVersion/La%20Femme-Renarde%20%28view%29.jpg)

![[thumbnail of Corset & bird 01.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/41.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Corset%20%26%20bird%2001.jpg)

![[thumbnail of La Femme-Renarde (view 02).jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/26541/46.hassmallThumbnailVersion/La%20Femme-Renarde%20%28view%2002%29.jpg)