KIVLAND, Sharon (2019). Die Holzdiebe. [Show/Exhibition] [Show/Exhibition]

Documents

22940:516412

22940:516423

Image (JPEG)

blackbird.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

blackbird.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (855kB) | Preview

22940:516424

Image (JPEG)

broom.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

broom.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (702kB) | Preview

22940:516425

Image (JPEG)

squirrel and fawn.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

squirrel and fawn.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (899kB) | Preview

22940:516426

Image (JPEG)

wall.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

wall.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (871kB) | Preview

22940:516427

Image (JPEG)

weasel and bird.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

weasel and bird.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (1MB) | Preview

22940:516428

Image (JPEG)

squirrel with pinecone.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

squirrel with pinecone.jpg - Other

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (1MB) | Preview

Abstract

In 1842 Karl Marx was twenty-four years old. This year is the bicentenary of his birth (5 May 1818), and here, we might also celebrate the birth of what came to be called Marxism. In October 1842 Marx wrote a series of articles for the Rheinische Zeitung, reporting on the proceedings of the Sixth Rhine Province Assembly, ‘Debates on the law of thefts of wood’, signing them ‘B., a Rhinelander’.

For many generations, the inhabitants of the Rhineland had been allowed to gather fallen branches for firewood, but now they were told that scavenging for elementary livelihood would become a crime against private property. The penalties for this would depend on the assessed ‘value’ of what had been free timber, determined by the putative ‘owners’, the value of what nature let fall to the ground. Marx’s polemics on this injustice contain the seeds of his work on the material structure of society and the distinction between use value and exchange value.

Raoul Peck’s recent film Le Jeune Karl Marx opens with the massacre of peasants collecting wood in the forest, presenting a primal scene of the philosophy of Marx, one might say. In the vote for the title of law, ‘even the pilfering of fallen wood or the gathering of dry wood is included under the heading of theft and punished as severely as the stealing of live growing timber’. Marx comments: ‘It would be impossible to find a more elegant and at the same time a more simple method of making the right of human beings give way to that of young trees’. He argues that the gathering of fallen wood and the theft of wood are quite different matters. Growing timber must be separated from its organic association in order to appropriate it, which is an outrage against the tree and thus also against the owner of the tree. However, in the case of fallen wood, nothing has been separated from property, for the wood is already apart from property as the owner of the tree possesses only the tree and the tree no longer possesses the branches that have fallen from it: ‘The wood thief pronounces on his own authority a sentence on property’.

Collectively, the animals of the forest rise up with an instinctive sense of right, gathering the alms of nature, their roots positive and legitimate. They resist that their customary rights should become the monopoly of the rich. They assemble and assert their rights. The stoats have news from France. They ask what property is and the birds reply that it is theft. The squirrels refuse any definition of property that privileges the wealthy, and propose a social solidarity. The weasels cry out that they are nature and nature is theirs alone. The fox maintains that a customary right by its very nature can only be a right of a lowest, property-less, and elemental class. The lynx and badger will fight against any plundering of the commons. None will accept punishment where there is no crime.

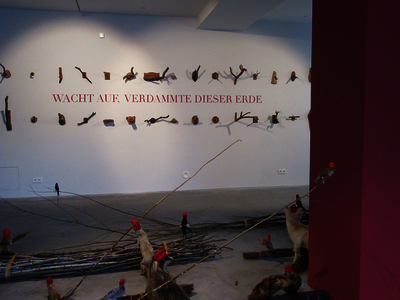

The exhibition is founded on Marx’s articles, and a number of commentaries thereon, in particular Daniel Bensaïd’s book Les dépossédés. The mise-en-scène is as follows:

The space suggests a forest, first, through three vignettes of woodland scenes painted in dark red on three walls. Each is derived from an illustration to one of the folktales collected by the Brothers Grimm, supposedly gathered from peasants though there is some indication that many stories came from bourgeois or aristocratic acquaintances, and supposedly reflecting Germanic culture, though many of the stories existed in many versions throughout Europe. The stories were revised and indeed, sanitised in later editions.

On the floor are bundles of wood, produced by a local forestry according to traditional methods: sizeable faggots or fascines, used to fuel ovens or to protect riverbanks, smaller faggots that might be used to make besom brooms (it may be noted that under article 66 of the law on thefts of wood, any citizen who buys a broom that is not issued under monopoly may be punished by hard labour from four weeks to two years), and pimps, bundles of kindling made with twenty-five small twigs tied with tarred string. On one wall are small branches and twigs, on which once some of the animals and birds below were mounted, and from which they are now liberated.

Climbing on and among the wooden bundles are a number of forest dwellers: a fox, a lynx, a badger, a pheasant, a partridge, some squirrels, a variety of songbirds, and a mob of stoats and weasels. The animals are stuffed, and as such are things, objects rather than the animate beings they once were. Yet they are brought again to life in this new encounter, capricious and resistant, endowed with life and sporting delightful Phrygian bonnets, the cap of liberty. In French, an animal subjected to taxidermy may be described as naturalised – that is, more natural than Nature, and to be naturalised is also to become a citizen. Originally the felt cap of the emancipated slaves of ancient Rome, the bonnet rouge was adopted during the Great Terror of the French revolution by all, even those who might be denounced as moderates or aristocrats, eager to demonstrate their adherence to the new regime. During the later uprisings in France of 1840 and 1848 the premier ministre Adolphe Thiers banned the wearing of the bonnet rouge, as a ‘seditious emblem, synonymous with anarchy and recalling unfortunate memories’.

Bensaïd ends Les dépossédés thus: ‘the question remains: selfish calculation or solidarity, property or the inalienable right to existence, which will prevail? Our lives are worth more than their profits: “Arise, wretched of the earth”.’

More Information

Statistics

Downloads

Downloads per month over past year

Share

Actions (login required)

|

View Item |

Tools

Tools Tools

Tools![[thumbnail of view.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/1.hassmallThumbnailVersion/view.jpg)

![[thumbnail of blackbird.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/6.hassmallThumbnailVersion/blackbird.jpg)

![[thumbnail of broom.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/7.hassmallThumbnailVersion/broom.jpg)

![[thumbnail of squirrel and fawn.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/8.hassmallThumbnailVersion/squirrel%20and%20fawn.jpg)

![[thumbnail of wall.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/9.hassmallThumbnailVersion/wall.jpg)

![[thumbnail of weasel and bird.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/10.hassmallThumbnailVersion/weasel%20and%20bird.jpg)

![[thumbnail of squirrel with pinecone.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/22940/11.hassmallThumbnailVersion/squirrel%20with%20pinecone.jpg)