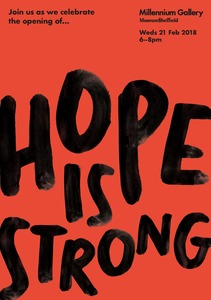

KIVLAND, Sharon (2018). Hope is Strong. [Show/Exhibition] [Show/Exhibition]

Documents

21374:475266

Image (JPEG)

Hope is Strong launch invitation_Page_1.jpg

Available under License All rights reserved.

Hope is Strong launch invitation_Page_1.jpg

Available under License All rights reserved.

Download (116kB) | Preview

21374:475269

21374:475270

21374:475271

21374:475272

Abstract

With far right parties and hate crimes on the rise, civil liberties and minority rights seem more at risk today than we could have imagined. In these turbulent times, Hope is Strong explores the power of art to question the world in which we live.

Hope is Strong features work by Conroy/Sanderson, Ashley Cook, Kate Davis, Jeremy Deller, Ruth Ewan, Jamie Fitzpatrick flyingleaps, Mona Hatoum, Sharon Kivland, Goshka Macuga, Ciara Phillips, Keith Piper, Olivia Plender, Hester Reeve, Sean Scully, Ai Wei Wei, and Artur Zmijewski.

Sharon Kivland exhibited a work entitled The Good Readers:

The Good Readers is a work that takes a number of formations, according to circumstances. It can be mobilised according to the situation. Here the foxes carry books by Marx in their jaws, each wearing the cap of liberty. The Paris sans culottes displayed their revolutionary ardour and plebeian solidarity in wearing the cap, which, during the Great Terror, was adopted even by those who might be denounced as moderates or aristocrats, eager to demonstrate their adherence to the new regime. They encircle a mannequin, a woman in miniature, a model woman, who has become a marianne. She is also, it would appear, half-fox. Marianne, symbol of France, that lovely allegory of the Republic of whom there is no single rule for her representation, is often shown wearing a Phrygian cap. When she wears the bonnet rouge, she is rebellious and popular. In 1793 she is war-like, fierce, liberty leading the people, hair streaming back, breast uncovered, fighting and victorious, as she is shown in Delacroix¹s painting of 1830, the year of the July revolution that led to a constitutional monarchy until the revolution of 1848. The men follow her. She is a symbol and she wears symbols; her bonnet is freedom. She is both an effigy and a principle, clad in a short tunic, in the style of antiquity. Her arm is raised with her fist clenched in a gesture of rebellion. She holds aloft a flaming torch to represent the light of progress. She incarnates the Republic and the people, liberty and reason. Under the Directoire she becomes rather more languid and assumes a draped classical dress, restricting her movement. In the representation of Marianne changes to one of the most bourgeois discretion; her breasts are modestly covered, she is sitting still, her bonnet is replaced by the rays of the sun. Two Mariannes are authorised. A bust is installed in every mairie; most frequently found in public buildings after 1870 is the bust after the model by Jean-Antoine Injalbert, a Marianne with the gorgon¹s head on her breast. Often in my arrangements, it is unclear if the foxes are the liberators and educators, or if there has been an act of violence, wrenching the book or another object (a silk negligee, for example) from a body or bodies by force, an exchange that the woman if she is a commodity cannot do for herself. The foxes, too, are things, objects rather than the animate beings they were once, yet they are brought again to life in this new encounter, capricious, sportive, endowed with life, like wanton women. Perhaps they are going to the market on their own, in their own right, and if so, then social organisation is subject to change (if the dead, animal or woman, starts to speak, moves, acts). Here it is evident that a mob has gathered, with an objective, and a symbolic leader (she is headless, of course).

More Information

Statistics

Downloads

Downloads per month over past year

Share

Actions (login required)

|

View Item |

Tools

Tools Tools

Tools![[thumbnail of Hope is Strong launch invitation_Page_1.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/21374/1.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Hope%20is%20Strong%20launch%20invitation_Page_1.jpg)

![[thumbnail of IMG_2751.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/21374/2.hassmallThumbnailVersion/IMG_2751.jpg)

![[thumbnail of IMG_2757.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/21374/3.hassmallThumbnailVersion/IMG_2757.jpg)

![[thumbnail of IMG_2760.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/21374/4.hassmallThumbnailVersion/IMG_2760.jpg)

![[thumbnail of IMG_2758.jpg]](https://shura.shu.ac.uk/21374/5.hassmallThumbnailVersion/IMG_2758.jpg)